THE SLEEPER AWAKENS: CONTEXT AND PRODUCTION

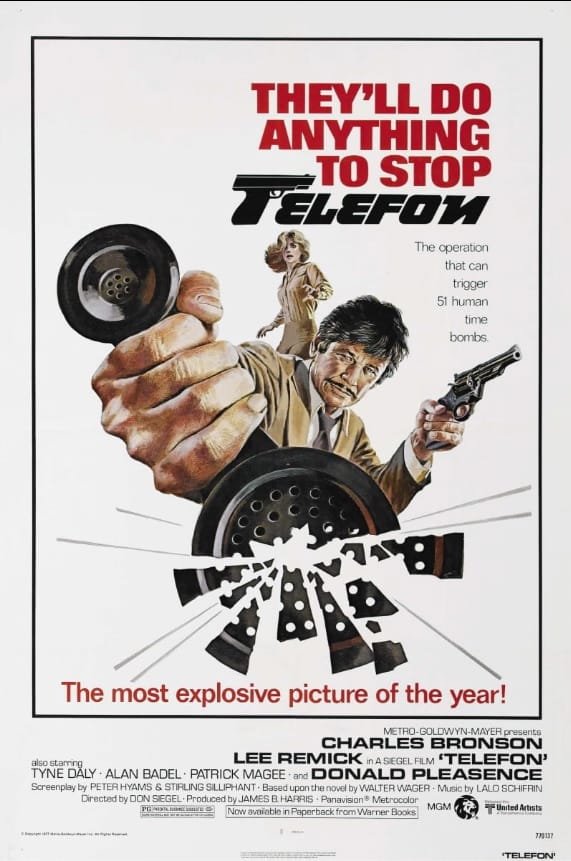

“Telefon” is one of the most fascinating yet criminally underseen entries in the Cold War espionage subgenre that flourished during the Nixon-Carter transitional period. Shot during the apex of détente—that brief window when US-Soviet relations thawed enough for diplomatic handshakes while the underlying machinery of espionage churned unabated—Don Siegel’s taut thriller emerged as an unintentional time capsule of late-70s geopolitical anxiety.

Behind the scenes, the film had a troubled production history that mirrors the conflicted political landscape it portrays. MGM acquired the rights to Walter Wager’s novel in late 1974, with Peter Hyams initially writing the screenplay with hopes of directing. After Hyams’ previous MGM project failed commercially, Richard Lester was attached before ultimately giving way to Don Siegel. In a telling reflection of the film’s themes of divided loyalties, Siegel himself admitted he was primarily interested in working with Charles Bronson and found the story didn’t “make much sense,” resulting in what some critics have noted as an uncharacteristically disengaged directorial effort.

What makes “Telefon” particularly noteworthy in Siegel’s filmography is how it serves as the spiritual midpoint between the paranoid surveillance aesthetics of “The Conversation” (1974) and the late Cold War jingoism that would later dominate Reagan-era actioners. The production took place during that liminal period when Hollywood was transitioning from the paranoid conspiracy thrillers of the early 1970s to the more muscular, action-oriented fare that would define the 1980s.

Bronson, fresh off his vigilante persona in the “Death Wish” series, delivers a remarkably restrained performance as KGB Major Grigori Borzov. He employs what Andrew Sarris might call “strained minimalism”—that peculiar acting technique where emotional withdrawal itself becomes a narrative device. The casting itself represents a fascinating meta-commentary: the quintessential American tough guy portraying a Soviet operative during a period when American audiences were being conditioned to view their Cold War adversaries with more nuance.

NARRATIVE DECONSTRUCTION AND SUBTEXT

The film’s premise—Soviet sleeper agents programmed to activate upon hearing Robert Frost’s poetry—functions as a delicious bit of psychological horror embedded within the espionage framework. This programming device bridges the gap between the brainwashing panic popularized in “The Manchurian Candidate” (1962) and the cognitive trigger concepts that would later influence films like “The Long Kiss Goodnight” (1996) and “The Bourne Identity” (2002).

What’s particularly ingenious about Siegel’s direction is how he frames the activation sequences with elements borrowed from giallo and proto-slasher aesthetics: the ringing telephone creating Pavlovian dread, tight close-ups on the agents’ faces as their programming activates, and the methodical, almost somnambulistic violence that follows. It’s psychological horror dressed in espionage clothing.

The subversive brilliance of “Telefon” lies in its central conceit: the most significant threat isn’t direct confrontation between superpowers but rather the weaponization of ordinary citizens. These sleeper agents—appearing as quintessential Americans—represent the externalization of internal Cold War paranoia. They embody the fear that anyone—your neighbor, your colleague, even yourself—could be an unwitting instrument of foreign destruction.

DÉTENTE CINEMA AND HISTORICAL RESONANCE

Released in December 1977, nearly a year into Carter’s presidency, “Telefon” reflects the contradictory impulses of the détente era. Carter’s human rights emphasis existed alongside continuing intelligence operations, creating precisely the type of geopolitical schizophrenia that the film depicts. The rogue KGB clerk’s actions—activating obsolete sleeper agents—serve as a metaphor for hardliners on both sides working to undermine diplomatic progress.

What distinguishes “Telefon” from contemporary Cold War thrillers like “The Spy Who Loved Me” (also 1977) is its resistance to cartoon villainy. The threat comes not from megalomaniacs with volcano lairs but from bureaucratic dysfunction and ideological zealots working within the system—a far more mature and politically literate approach to espionage cinema.

Cinematographer Michael Butler’s work deserves special mention for its documentary-adjacent visual approach. It utilizes existing light sources, practical locations, and a desaturated color palette that feels distinctly American yet somehow infused with Soviet visual aesthetics. This visual strategy creates a disorienting effect, making American landscapes feel subtly alien, reinforcing the narrative’s themes of hidden threats in familiar settings.

PERSONAL REFLECTIONS: VIEWING AND REVISITING TELEFON

I first saw “Telefon” during its original theatrical run in 1977, drawn primarily by the star power of Charles Bronson, Lee Remick, and Donald Pleasence. As a filmgoer of that era, I appreciated the film’s more restrained approach to Cold War tensions compared to the bombastic spy adventures that dominated the decade. The performances impressed me, particularly Bronson’s understated turn as a Soviet agent—a dramatic departure from his vigilante persona that had, by then, come to define his career.

Stirling Silliphant and Peter Hyams’ screenplay (adapted from Walter Wager’s novel) attempted to inject nuance into what could have been a straightforward thriller, though the final product bears the marks of its troubled production history. As later revealed, the script went through multiple iterations as directors changed, with Siegel ultimately working from Silliphant’s version rather than Hyams’ original draft.

Revisiting the film now offers a fascinating case study in how cinema both reflects its era and ages in unexpected ways. While the geopolitical anxiety and paranoia still resonate, other aspects—particularly the gender dynamics—reveal themselves as products of their time.

GENDER DYNAMICS: REVISITING COLD WAR CINEMA THROUGH A MODERN LENS

Watching “Telefon” upon its release in 1977, the romantic subplot between Remick’s Barbara and Bronson’s Borzov seemed like standard narrative procedure, an expected element in the espionage formula.

Revisiting the film decades later reveals the stark evolution in how we perceive gender dynamics in action thrillers. Remick’s performance remains solid, but the character’s rapid pivot from capable intelligence operative to romantic interest feels jarringly out of place through contemporary eyes. Dialogue exchanges like:

Barbara: “If, I mean when, we get Dalchimski I suppose you’ll be going home. You going home to anyone, I mean, do you have a wife?“

Borsov: “No.“

Barbara: “Lucky girl.“

Barbara: “I know, I talk too much.“

These lines, delivered by a supposedly seasoned agent to a foreign operative she’s just met during a high-stakes mission, illustrate how female characters in this era were often undermined by screenwriters who couldn’t imagine women existing in action narratives without romantic entanglements. This aspect of “Telefon” serves as a time capsule not just of Cold War anxieties but of Hollywood’s limited imagination regarding female characters in the pre-blockbuster era.

The film’s treatment of Remick’s character echoes its own production struggles—talented contributors constrained by the conventions and expectations of their time. This tension between capability and convention makes “Telefon” an even richer text for understanding the cultural transitions of the late 1970s.

PARANOIA THEN AND NOW: THE EVOLUTION OF ESPIONAGE ANXIETY

| Aspect | 1977 Context (Cold War) | Today’s Context (2025) |

| Geopolitical Rivalry | US vs. USSR, détente efforts, nuclear arms talks | US vs. Russia/China, cyber warfare, trade wars |

| Espionage Methods | Physical sleeper agents, phone-based activation | Cyber espionage, digital infiltration |

| Internal Threats | Post-Vietnam, Watergate, and civil rights | Homegrown terrorism, radicalization online |

| Manipulation | Brainwashing, coded phrases | Disinformation, social media propaganda |

| Social Climate | Polarization, racial tensions, and security debates | Polarization, racial tensions, security debates |

This table illuminates the diachronic evolution of “Telefon’s” central anxieties—a virtual Rosetta Stone for decoding how the paranoiac subtexts of Siegel’s film have morphed yet persisted across decades. What’s particularly striking is how the activation methodology has shifted from the analog (telephone calls, poetic triggers) to the digital (algorithms, targeted propaganda) while the underlying mechanics of control remain eerily consistent.

MODERN PARALLELS: FROM SLEEPER AGENTS TO CYBER WARRIORS

The film’s central concern—foreign powers activating destructive agents within American borders—finds eerie resonance in contemporary security concerns. The 2010 discovery of the Russian “Illegals Program” (which inspired “The Americans”) validated “Telefon’s” premise decades later, proving that deep-cover operations weren’t merely Cold War fiction but operational reality.

Where “Telefon” employed telephone calls and poetry as activation methods, modern equivalents utilize digital infrastructures for recruitment, radicalization, and operational control. The brainwashed agents of Siegel’s film find their contemporary counterparts in everything from state-sponsored hackers to individuals radicalized through online propaganda—all “sleepers” until activated.

The film’s narrative structure—essentially a cat-and-mouse pursuit between competing operatives across American territory—established a template that’s been remixed countless times in post-9/11 espionage cinema. The motif of internal threats hidden in plain sight has evolved from Communist infiltration fears to terrorism anxieties to today’s concerns about digital manipulation and election interference.

CULTURAL AFTERLIFE AND GENRE INFLUENCE

Although overshadowed by more flamboyant spy entries of its era, “Telefon” exerted a subtle influence on subsequent espionage narratives. Its DNA is evident in everything from “The Americans” to some aspects of the “Jason Bourne” story. The film’s central MacGuffin—the “Telefon Book” containing agent identities—prefigured similar plot devices in “Mission: Impossible” and countless other spy properties.

The film’s most lasting contribution might be its fusion of psychological horror mechanics with traditional espionage structures—creating a hybrid approach that would later flourish in films like “Jacob’s Ladder” (1990) and “The Manchurian Candidate” remake (2004). By centering its narrative on the erasure and manipulation of identity, “Telefon” helped bridge Cold War espionage cinema with the identity crisis thrillers that would dominate post-Soviet spy films.

For cinephiles tracking the evolution of espionage cinema through its key transitional works, “Telefon” stands as a crucial missing link—the moment when the paranoid conspiracy thriller began evolving toward the action-oriented spy spectacles of the 1980s while maintaining the psychological complexity that distinguished the best 1970s cinema.

In that sense, “Telefon” isn’t merely a time capsule of détente-era anxieties but a prescient text that anticipated the evolution of both espionage cinema and actual geopolitical concerns. Its sleeper agents, waiting for activation, serve as the perfect metaphor for dormant cultural anxieties that never truly disappear—they merely wait for the right moment to reawaken.

Please note that some or all links in this article are affiliate links. “As an Amazon Associate, I earn from qualifying purchases.”